I’ve previously argued that you should default to pricing things higher rather than lower. The practical reason is simple: assuming all players see the same prices, making things cheaper means your most engaged users – those with the highest propensity to spend – will spend less. And you probably won’t make up that revenue with increased conversion. Don’t take my word for it; AB test it. But in my experience, unless the initial pricing was dramatically off, I haven’t seen conversion increases compensate for decreased ARPPU (average revenue per paying user).

There’s a more fundamental reason why higher pricing often works better.

The Foundation: Players Pay for Feelings, Not Value

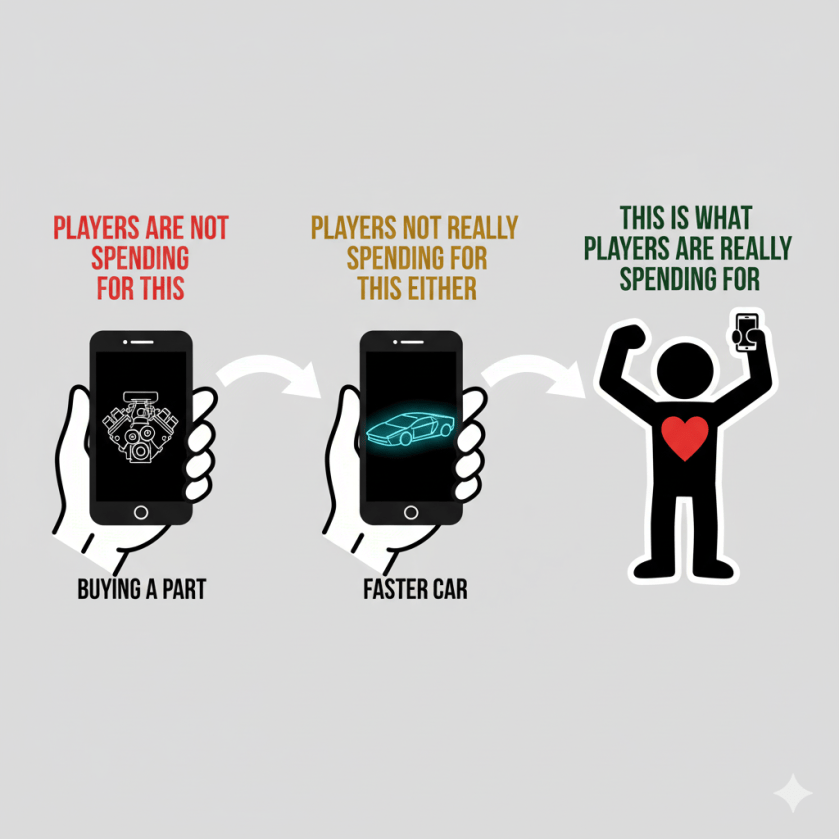

Everything you sell in your game is worthless. Not “low value” – literally worth nothing. There’s no material cost, no scarcity, no manufacturing overhead. Understanding this paradox is the key to profitable monetization.

The items you’re selling have no intrinsic value. There’s zero delta in cost whether you sell 1 or 1,000,000 items. The price of in-game items is completely disconnected from any objective value (which, for simplification, we can assume is zero). You’re attracting players with the promise of free entertainment, and what you’re selling is superfluous by definition.

Calling any purchase in a mobile free-to-play game a “rational decision” is a stretch. Players aren’t spending money because they need what you’re selling. They’re spending because they like your game and they’re having a good time. They are paying for feelings. Buying in-game items or functionalities is a means to an end, and that end is always emotional: satisfaction, pride, progress, status, joy, relief.

If you haven’t read it, check out “The Motivational Pull of Video Games: A Self-Determination Theory Approach” – it’s essential reading for understanding player motivation.

This perspective matters because it changes everything about how you should approach pricing.

The Pricing Principle: Start From Players, Not Items

If the things you’re selling have no intrinsic value, and players are spending for feelings, then you need to start from your players to define pricing – not from the things you’re selling.

Don’t price things in terms of what they’re worth. Price things in terms of what players are willing to spend for them.

Here’s the process:

- Start with the audience segment you’re targeting

- Define the price point you want them to spend at

- Put into the bundle what’s needed to justify that spending

- Optimize for revenue maximization, not some notion of “fair value”

Set targets based on player behavior: How much should players spend to complete an event? How much time and money to max out a character? But base these targets on what players are actually doing and how they engage with your economy, not on arbitrary item values.

Making Spending Feel Good

If players are spending for feelings, you need to ensure spending money in your game feels good. There are two proven ways to achieve this:

- Spending is immediately gratifying

- Spending provides entertainment value beyond the purchase moment

And if you want players to spend more rather than less, you need to ensure that relatively speaking, spending more feels even better than spending less.

This means two things must be true:

a) Spending feels better than not spending

b) Spending more feels better than spending a little

The first is primarily about game and monetization design: How do you design the item and experience so that having it is meaningfully better than not having it?

The second involves game design – how is the experience with multiple items qualitatively better than with one item? – but also includes a critical pricing consideration: How much more impactful is increased spending?

You want the impact-per-dollar ratio to increase as players spend more, not just remain constant. This is where bundle structure becomes crucial.

What This Means for Your In-Game Shop

When you price your shop, remember: your gems have no intrinsic value, just like your items.

The lowest price point serves two critical functions:

- It attracts a large portion of purchases (so don’t price it too low)

- It anchors the perceived value of your currency

All other bundles have one function: They’re decoys meant to drive purchases toward higher price points.

The Discount Progression Structure

You need to optimize two metrics at each price tier:

- Absolute value improvement: Each bundle should offer better $/gem value than the baseline

- Relative value improvement: The rate of improvement should increase as bundles get more expensive

Here’s what this looks like in practice:

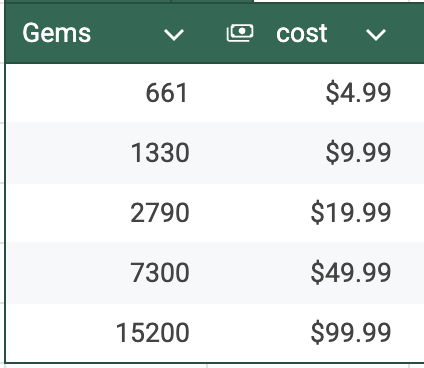

One simple thing here is to look at the $/gem value, and how that value improves as bundles get more expensive.

Here you can see that gems become gradually cheaper as players buy higher bundles. The gem price at $9.99 is lower than the basic gem price. Same for the $19.99, $49.99 and $99.99 bundles. So that’s good. Kinda – not sure what’s behind the 0.5% decrease when purchasing the $9.99 bundle vs. the $4.99 one. You’re almost encouraging the player who wants to buy to get the $4.99 bundle.

Another thing that’s worth looking at is the rate of improvement. What is the rate of discount from one bundle to the next? Here you see many games don’t have an improving rate of increase. Between the $19.99 bundle and the $9.99 bundle, the $/gem price decreases by 4.6%. Between the $49.99 and $19.99 it decreases 4.4%. Not only is the improvement not better, it’s worse

I played around with Gemini and put together a simple “bundle generator” so your game can focus on having bundles that are a) gradually better compared to the anchor price and b) are relatively better as players spend more.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Flat discount curves: Many games offer consistent improvements (e.g., 5% better at each tier). This doesn’t create sufficient motivation to jump to higher tiers.

Rounded numbers that signal arbitrary pricing: Bundle values like 2,790 or 15,200 gems suggest pricing was grounded in some imagined intrinsic value of gems rather than player psychology. Use clean, memorable numbers that communicate value: 2,900 or 15,500.

Minimal differentiation at low tiers: If your $4.99 and $9.99 bundles offer similar value, you’re training players to always choose the cheaper option.

The Same Principle Applies to Progression Design

Beyond shop pricing, this philosophy should guide your entire monetization strategy. If you want your game to monetize, follow these two rules:

- Spending provides a better experience than not spending

- Spending more provides a better experience than spending less

Design your progression in layers for three distinct experiences:

- Layer 1: Non-payers

- Layer 2: Low spenders

- Layer 3: High spenders

Each layer should feel more rewarding and fun than the previous one. The feeling players get at each level – not the functionality of what they receive – should be your guiding principle.

Facilitate Graduation Between Tiers

Balance your game to:

- Identify the moments most conducive for players to graduate from one tier to the next

- Create the conditions that get the maximum number of players to those progression moments

- Make the jump feel worthwhile through both immediate gratification and sustained benefit

A sustainable live ops system requires that content consumption aligns with your production velocity, but that’s a topic for another post.

Key Takeaways

1. Anchor pricing in player behavior, not item value

Your items and currency have no intrinsic worth. Price based on what players will pay for the feelings you’re creating.

2. Make the shop tell a story

Your bundle structure should communicate that spending more is increasingly rewarding. Use accelerating discount curves, not flat ones.

3. Design in layers

Create distinct experiences for non-payers, low spenders, and high spenders. Make each tier meaningfully better than the last.

4. Test, but test strategically

Higher prices usually monetize engaged users better. When testing price decreases, watch whether conversion gains actually offset ARPPU losses (they usually don’t).

5. Optimize for feelings, not fairness

Players aren’t making rational economic decisions. They’re choosing how to feel. Your job is to make spending feel great—and spending more feel even better.

What matters isn’t how many gems you’re giving out. It’s how many players are spending in your game, and how much those who love your game are willing to invest in their experience.

Price accordingly.

One comment