Disney Solitaire came out a few months ago and seems to be performing pretty well in the top grossing ranks. I’m a fan of Solitaire games so I jumped on this one. The more I played it, the more I think it’s top class when it comes to managing and monetizing failure. And most games (solitaire or not) would benefit from implementing a similar logic. Obviously, your game needs to have fail conditions for this to be relevant. So merge or coloring games probably won’t lend themselves as naturally to this kind of feature. But pretty much any game with a fail condition can easily learn from this. To be clear, Disney Solitaire did not create this feature. But playing the game is what made me want to write this post – so I’m using it as an example. But there have been others before that.

User-initiated continue or user-initiated failure

In most games, failure happens automatically. You run out of moves or your character dies and a pop up automatically surfaces and informs you you lost and the game is over (and ideally prompts you to spend to continue). It’s pretty standard for a game to proactively tell players they have failed. The game stops and tells players it’s over – unless they spend to continue. Here, the default state is “game over” and players must initiate continuing the game.

Disney Solitaire does something else. Very well. Like all solitaire games, the point is to clear the cards on the table. Players draw a card from a deck and the cards on the table on it (for example, you can only put a 6 on a 5 and a 7).

If players can clear all the cards on the table they win. If they run out of cards in the deck and there are cards left on the table the game is lost. So there is indeed a moment in gameplay where players can’t continue playing because they are out of cards to draw and there are cards left on the table. But the way most solitaire games manage that moment, and the way in which the “game over” screen is displayed is very different. That’s what I call “user-initiated failure”. The game never automatically triggers a “game over’ state. The game is only over after players have chosen to quit.

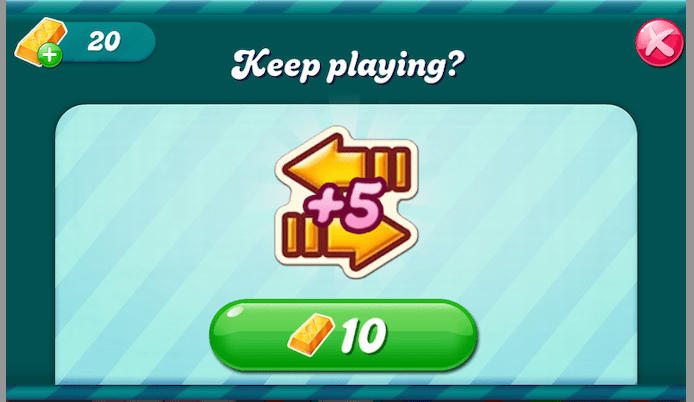

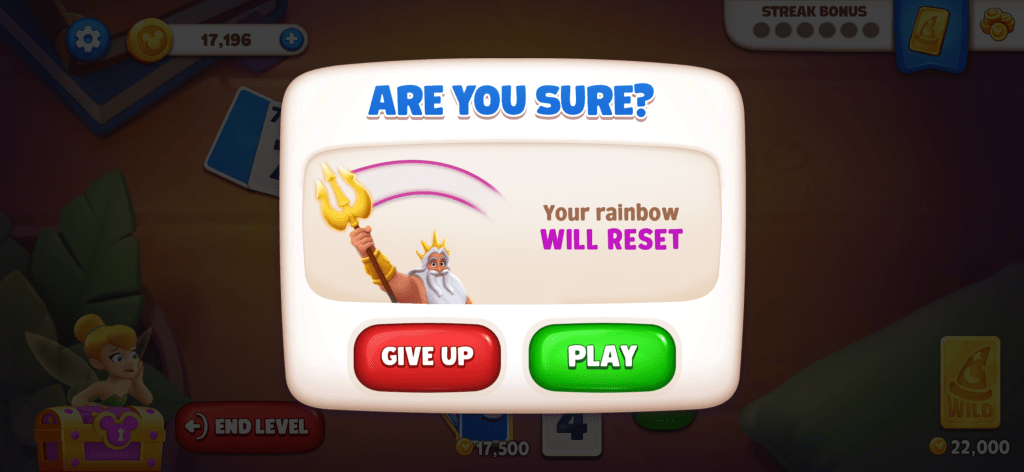

If players can clear the board, a “win” popup is automatically surfaced. But if they draw the last card in the deck and there are cards left on the table. There is nothing they can do except spend to prolong the game (in the case of Disney Solitaire: undo, buy 5 more cards, or buy a wildcard) or end the level. And the game remains in that state until players make a purchase or end the game. When players click “end game”, there is a confirmation message (bonus points for a compelling streak feature to make falling even more comfortable – I feel like something better could be done here in Disney Solitaire).

What’s interesting here is how the game flips the traditional script around failure. Disney Solitaire will not tell users they failed. In Disney Solitaire, players are never automatically faced with a game over screen. Instead of saying players failed and prompt them to continue, the continue options are always present – continue and spending is the default option, not “game over”. And what this means is the game places the burden of failure on players if they don’t want to spend to continue.

There is something very strong here from both a psychological and structural point of view. Psychologically, users are the ones who must quit. Acknowledge their defeat. And that changes the traditional relation to failure in games. The game doesn’t say players failed. Players must give up. In addition, Disney Solitaire does a great job at pricing their continue (the wildcard) in a way that drives players to spend. At the same time users have to decide to quit the game, they are confronted to a very compelling cost-benefit calculation. There is a strong incentive to buy the wild card to complete the level – rather than continue and spend to try the level again.

Pricing a compelling continue option

In conjunction with the user-initiated failure, Disney Solitaire does a great job at creating a very compelling cost-benefit calculation to pay to complete levels. This is because players spend the same currency to initiate a level and to continue playing. If you use different currencies to play (for example, energy) and to continue (for example, gems) then you can still do something similar but it probably won’t be as compelling.

From a structural point of view, Disney Solitaire does an amazing job at pricing their wildcard and appealing to players as economic agents to incentivise spending. If you’ve played the game enough you’ve experienced how much economic sense it makes to spend on a wildcard when you’re only one card away from beating a level. It makes much more sense to buy a wildcard than to quit and replay the level – even if it costs more.

Players spend to initiate a level. Say 10400 coins. When there is only one card left, using a wild card guarantees a win. The wild card is a bit more than 2x the cost of initiating a level. Say 22000 coins here. Now, combining the user-initiated failure with the wildcard is a great combo that surely drives a bunch of spending. Both spending that depletes players’ balance (which is super important for a healthy economy) and IAP spending.

When I have only one card left, I can choose to quit the game. But I know it will cost at least 10k to replay the level – with no guarantee I will actually beat it. So automatically, no matter what, quitting a level carries a 10k cost next to replay the level. What this means, is that you’re not comparing spending the 22k for the wild card to spending 0. Initiating failure means you are choosing between spending 10k coins for a future (uncertain) attempt and spending 22k coins for a guaranteed win. So the wildcard is not really worth 22k coins. Rather, in this case, the cost of a guaranteed win is 11600 coins.

Quitting is accompanied by an economic choice – spend again and take a chance to beat the level, or spend a bit more for a guaranteed win. So in a way this fits into the “monetization tied to gameplay” model. And optimizing performance here probably means optimizing for “only 1 card away” moments

Using this is other games

What could that look like in your game? In this post I talk mostly about function. And ideally once the OKRs are defined, people with a better creative sensitivity than myself can come up with more sophisticated and refined solutions. If the currency you use to initiate a level and the currency you use to continue playing is the same, even better! You can balance your continue cost in a way to be super optimal.

I’ll just give a few (super functional and very raw) examples below of what that could look like:

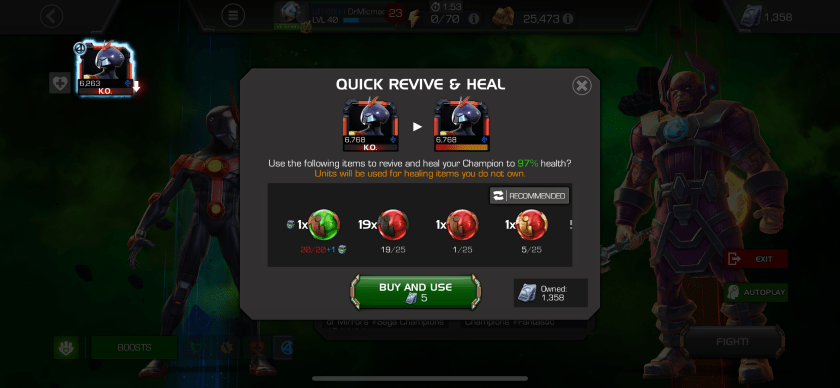

- Imagine in an RPG you are in a fight there is a timer and/or HP for your character or squad. Once you’re out of time or HP, instead of having a “fail” popup, the screen is in statis. Players have the option to pay (or use consumables) to add HP or time. If users don’t want to, they can click the “give up” button. Contest of Champions is a great example of that. Surprizingly, there aren’t more

- Take a tile match game. When the tile tray is full, instead of prompting players with a fail “out of space” popup leave the board as in. And introduce an option to “destroy” a trio of tiles or increase the side of the tile tray. Or players can choose to end the level.

- In a match 3 game, when players are out of moves, they have the option to buy more moves, use a booster, or give up (you probably want to work the standard UI in the genre here so the number of available moves is front and center so users have an acute sense of being at 0 moves)